Golf Fashion for Female Golfers & Spectators, 1800–1899

- cathylane1118

- Feb 10, 2023

- 25 min read

Updated: Mar 13, 2023

Women golfers at St. Andrews, 1868 (University of St. Andrews archives.)

The following article and its brother, "Golf Fashion for Male Golfers and Spectators, 1800–1899," were inspired by a vlog created by Christian Williams, aka The Hickory Hacker. Even though Christian is talking about men’s clothing, the lessons he has learned in his extensive historic golf experiences are extremely helpful. We suggest viewing the vlog first, then diving into the article.

This article covers 1800 to 1899. The featherie era ended with the introduction of the gutty ball in 1848, and the gutty era ended in 1899, when the Haskell ball was patented.

One of the most common questions people new to historic golf ask is, “What do I wear?” The answer is, of course, “It depends.” What decade or person do you want to emulate? What is your budget? Are you playing, watching, or perhaps helping at an event? What will the weather be like?

The goal in dressing for a featherie or gutty event is not simply to look “old-timey.” By wearing an era-appropriate outfit, you are making the event and experience better for yourself and others. You gain a better appreciation of history and (we hope) have more fun.

It’s unlikely that you will be able to find actual antique clothes that are in good enough shape to wear. Instead, look to companies that make historically appropriate clothing (there's a list at end of article). Or, modify modern clothing using the visual cues outlined in this article. Tailors can be extremely helpful.

Fashion changed wildly in the 19th century, especially for women. To help sort out the many options, we’ve tried to gather basic visual cues that you can use to kit yourself out in style, comfort, and historical accuracy.

Please consider the following while reading...

1. These are informed suggestions, not rules.

2. There would have been crossover between fashion eras: that is, people did not throw out their featherie-era golf clothing when the gutty ball happened along.

3. This article suggests clothing that would be worn while playing or watching golf, not for fancy dress or hanging around the house. But remember that featherie golf was largely a sport for the privileged, who had enough leisure time to play and money to afford “sporting clothes” and the equipment. The gutty era opened up golf to people of more modest incomes and wardrobes.

4. Between 1800 and 1899, most golf in the world was being played in the British Isles, so that is where our fashion research resides as well.

5. Underneath your old-style outfit, go modern. We strongly recommend an under-layer of merino wool for cooler weather and sweat-wicking materials for warmer weather. Both will keep you more comfortable and protect the investment you are making in your outfit.

Women’s Golf Fashion: 1800-1810

At this time, women were not involved in golf in the same numbers as men.

There is written evidence of golf or golf-like games that existed for hundreds of years prior to 1800, and only a sprinkling of female participants are ever mentioned (and some of them may have been playing the golf-like games). One mention of actual golf was in 1738, when two women and their caddy-husbands played on Bruntsfield Links in Edinburgh. In 1795, women who worked in the fish trade in Musselburgh, Scotland, were reported to play golf on their days off.

So some women were definitely playing golf, and they definitely didn’t begin on the very day historians noted it.

What did they wear? Women of modest means may have owned only two outfits—one for everyday and one for special occasions. Women of means would definitely have had a larger wardrobe, and some may have had “sporting clothes” for archery, swimming, or horseback riding. But women did not have “golf clothes”—they just made do with what they had.

This is the only decade of the 1800s in which woman’s clothing could have allowed the movement of a full golf swing. The excavations of Pompeii and the Herculaneum in the 1700s had inspired a keen interest in Greek and Roman antiquity. The result in women’s fashion was a much more relaxed, draping garment that revealed the shape of the human body instead of camouflaging it.

This 1802 illustration shows how the chemise dress mimicked dresses

seen on Greek and Roman statuary. (WikiCommons)

Dresses

The chemise dress was inspired by classical marble statuary of ancient Greece and Rome that showed loose, flowing garments. In fact, many dresses of this time are white or light-colored because the statues were made of white marble. This dress had a high waist (today called an empire waist—this was the Empire period) cinched right under the bust, and was made with lightweight, draping cotton muslins. These dresses had a long, vertical line, which created a slim silhouette. This was a style that women of lesser means could also accomplish, but with cheaper fabrics.

These dresses left more of the chest and back exposed. The front neckline was often squared off. Sleeves were kept short and puffed.

1800s dress. (WikiCommons)

The same empire-waist style, worn by an upper-class woman and a working-class woman. (WikiCommons)

Undergarments

In the “brother” to this article, Golf Fashion for Male Golfers and Spectators, 1800–1899, there is no mention of undergarments because they aren’t relevant to men's clothing styles. Unfortunately for women of this time, undergarments ruled fashion, or at least the shape it. For this period, some women wore stays or a corset underneath their dresses (this supported the bust), while some disposed with it. The slimmer cut of the dresses likely required only one petticoat beneath for decency—some of the dress fabrics were quite sheer—with perhaps a bustle pad on top of that.

Hats/headgear/hair

Emulating Grecian styles, women tied their hair up in a loose bun, with short, loose curls around the face. Sometimes a headband or jeweled combs were added.

In public, hats were mandatory for women. At this time, there were many options, including wide-brimmed bonnets, poke bonnets, and veiled caps.

A selection of hats from 1805. (Art: candicehern.com)

Stockings and shoes

Women’s stockings would have been white. Low-heeled shoes, ballet flats, or laced-up sandals were in style.

Accessories

Brightly colored and patterned shawls or stoles draped loosely over the elbows complimented the Grecian look. Out-of-doors, most women used a parasol, and short-sleeved dresses required long gloves.

Outerwear

The lightweight materials used in women’s dresses usually required a coat for outdoor activities. A pelisse, or front-opening coat, with long sleeves was fashionable. Its silhouette was similar to that of the dress.

Coats of this era had a silhouette that was the same as the dress underneath. (At left: Napoleon and The Empire of Fashion, and at right: The V&A.)

1810–1820

In 1811, there was the first record of a women’s golf competition with prizes at Musselburgh Golf Club, although it was on a pitch-and-putt course. Still, it’s indicative that women were playing in greater numbers. It's likely women golfers were still making do with their street wear.

The Postal Directories of Edinburgh made record of a female golf club-maker in 1820, a definite anomaly in social and golf norms for the time. Mrs. Isobel Denholm continued with her husband’s club-making or perhaps club-repair business at Bruntsfield Links after his death.

In fashion, the influence of classicism began to be influenced by other world events, such as the Napoleonic Wars, which brought in styles from Prussia, Poland, and Russia, including the use of fur on clothing.

Dresses

Dresses were still high-waisted, but their silhouette started to be interrupted by trims, flounces, tucks, and lace along the hem. Skirts also became more triangular by the end of the decade. Drapey trains of the 1810s disappeared when the hemline was raised to just above the floor. Necklines could either be square or V-shaped, but the emphasis was on angularity.

Sleeves began the 1810s straight, but eventually became fuller near the shoulder, turning into a full puff by the end of the decade. Long sleeves would be normal for daytime wear.

A variety of 1810 dresses and hats.

Undergarments

Corsets and stays still supported the bust. Some stays went over the hips, which created a willowy silhouette but certainly would not have allowed for much twisting or bending of the body. The more triangular skirt shape was supported with petticoats and a bustle pad.

Hats/headgear/hair

Hairstyles were normally parted in the center, with ringlets near the face and bunches of curls at the back of the head. For outdoor wear, bonnets and poke bonnets were the norm, and these grew in height and trimmings as the decade progressed. Some hats were inspired by military styles.

A selection of 1815 hats.

Stockings and shoes

White stockings and pointed flats and ballet flats would have been the norm.

Accessories

Wealthy women would have worn Kashmiri shawls, but there was a market for lesser-cost imitations, many of which were produced in Paisley, Scotland.

Other accessories would have included a purse and, for outdoors, a parasol in sunny weather or a fur muff and/or stole for colder weather.

Outerwear

The pelisse, or front-opening coat, was still in style, but women also began wearing a cropped jacket called a spencer. A pelisse-robe, or coat-dress, that could be worn by itself would also have been suitable for outdoor wear.

A pelisse with military styling. (The Kyoto Costume Institute.)

1820–1830

Between 1820 and 1825, the Neoclassical period ended, and the age of Romanticism began. This was a time when people valued freedom of expression and emotion in art, literature, music, and fashion. The Romantic era, which lasted until 1840, basically reversed Neoclassical fashion. People were inspired by the aesthetics of older, even medieval times.

Dresses

As a result, the entire cut of a woman’s dress changed. Instead of a slim silhouette, now skirts arched away from the body, with the waistline dropping back to normal waist level. Sleeves began the decade as puffs, then became huge poofs or mutton legs just off the shoulder, which then ballooned out to the entire sleeve. All of these styles mimicked dresses from the 13th to 17th centuries.

Skirts were usually gored (cut in an A-shape) with the narrowest part near the waist and the widest part near the floor. By end of the 1820s, this cut was replaced by a skirt made of panels, with tiny pleats that drew in the fullness at the waistband. Skirts could be decorated with flounces, lace, embroidery, and satin trim.

White fabrics were still popular, but brighter primary colors were also coming to the fore, as well as earth tones such as olives, browns, and grays.

Dress shape changed in the 1820s. A slim silhouette (left; Kyoto Fashion Institute) was replaced with a fuller skirt, fuller sleeves, and a lower waist (center and right; both The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Undergarments

Petticoats supported the bell-shaped skirt, while sleeve-plumpers kept the sleeves “inflated.” Corsets supported the bust.

Hats/headgear/hair

Hair was parted in the middle with elaborate curls over the temples. A looped knot of hair was often styled on top of the head. Hats also became more and more elaborate and were covered with flowers, plumes, ribbons, and jewels. Bonnets, wide-brimmed hats, and turbans were popular.

A selection of 1820s bonnets.

A variety of 1820s hats.

Stockings and shoes

Flat slippers were still in style. In the late 1820s, the first boot-like shoe caught on. It laced up on the inner side and had a narrow, squared toe. Stockings were generally white and held up over the knee with garters or ribbons.

Accessories

Wide matching belts with decorative buckles were common accessories. A perline, or capelet, made of white muslin, lace, or even the same fabric of the dress, was sometimes added to cover the shoulder and upper chest. Purses, parasols, and draping capes were also common.

Outerwear

Women wore full-length pelisse coats, some of which were trimmed with fur. Some women carried matching muffs, which could be huge. Shawls and cloaks were also common.

An 1821 illustration of a woman in a full-length pelisse.

(Credit: Claremont Colleges Digital Libraries.)

1830–1840

Women’s golf was growing during this period. Several sources report that as early as 1830, women played on a small four-hole course to the right of what is now the 17th green on the Old Course at St. Andrews. But records don’t yet note the existence of ladies golf clubs or organizations. In fact, many men at this time would consider females who played golf as unfeminine at best and of loose character at worst.

Queen Victoria ascended to the British throne in 1837, marking the start of the Victorian era. But societal and fashion changes attributed to her reign don’t start appearing until about 1850.

This is the earliest surviving photograph of a woman, Dorothy Catherine Draper, taken in 1838 or 1840. It shows many style attributes of the 1830s. (Public domain photo.)

Dresses

The Romantic Era was in full blaze in the 1830s. With plenty of width at the shoulder and a very full hemline, women’s dresses looked like two triangles meeting at a narrow waist. Sleeves were very full: the leg-o-mutton style featured a large, puffed sleeve on the upper arm and a slim sleeve on the lower arm.

Necklines were wide and round or V-shaped, and sometimes were worn with pelerines, large white lace or embroidered collars that extended over the shoulders and down the front of the dress. The V-neckline combined with huge sleeves created a sloping shoulder effect that was considered very feminine at the time.

Until about 1835, dresses could be ankle-length, but hems continued to drop into the 1840s.

At left: A selection of fashionable early 1830s dresses. Center: A 1830s walking dress. At right: A 1838 transitional dress shows how the fullness of the sleeves descended along the arms while a defined bodice elongated to just above the natural waist. (Left and center photos: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; right photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Undergarments

The tiny waistline of the dress required stays or corsets for slimming, plus voluminous starched petticoats that made the waist look even smaller by comparison. A small bustle pad could be worn at the back of the waist. Finally, the full sleeves were filled with sleeve plumpers that were stuffed with down.

Hats/headgear/hair

Hairstyles at this time were definitely creative. Hair was parted at the center and elaborately curled. Braids were looped around each ear and gathered in a bun or top-knot, sometimes with plenty of curls all around.

Wide-brimmed bonnets with high crowns were popular, as were hats with semi-circular brims. These head coverings were elaborately decorated with all manner of trim, ribbons, velvet, and feathers. Women wore hats for protection from the sun and weather, but hats during this decade were also aggressive fashion statements.

Bonnets and hairstyles of the 1830s were highly elaborate. The bonnet below is an example of a much more modest model. (Both samples: Vintage Dancer.)

Stockings and shoes

Low or no-heeled, square-toed slippers were common. Low boots that were held on with elastic became available.

An early form of the sneaker or tennis shoe was developed in England in the 1830s. A canvas shoe top was fused to a vulcanized rubber sole. The shoe was held on by a T-strap and buckle.

Stockings, which now were embroidered and sometimes quite wild in their patterning, were generally held up by a ribbon or garter above the knee, although elastic was being used in these as well.

Accessories

Wide belts were worn to accentuate the narrow waist. Purses and parasols were carried and gloves were worn in public.

Outerwear

Outside, women wore full-length mantles or mantelets (a shorter version of the mantle).

A French mantle from the 1830s. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

1840–1850

Two factors made tartan fabrics very fashionable in the 1840s: Queen Victoria had a new royal residence in Balmoral, Scotland, and even before she ascended to the crown, Victoria had a penchant for wearing plaid. Also, Walter Scott’s novels, which were set in Scotland, were very popular. So Scottish style was very much in vogue. Tartans continued to be in style into the 1860s and beyond.

Hand-colored etching of a female golfer, 1840.

Dresses

Dress fashion in the 1840s included bell-shaped skirts that grew larger through the decade. They had a low, pointed waist and long, tight sleeves that fit low on the shoulder, creating a demure, sloping effect. The sleeves in particular kept women from lifting their arms above their ears—certainly not conducive to developing a golf swing.

The bodice and skirt of dresses at this time were usually one piece, although jackets were also added. Additional flounces were sometimes added to skirts, but dresses were usually quite plain.

A variety of styles of 1840s dresses. (Credits: at left, [1848] The Metropolitan Museum of Art; center, [1840] National Gallery of Victoria & Albert; right, [c. 1845–48] Galleria del Costume di Palazzo Pitti.

Undergarments

Tight foundation garments such as stays and corsets were a necessity under dresses at this time to create the very slim, pointed waistline. They also prevented women from bending over, an action that was considered quite gauche. Petticoats created the bell-shape of skirts; often many layers of petticoats were needed as the decade progressed in order to create more and more volume.

Hats/headgear/hair

Women parted their long hair in the middle and swept it back over their ears to a bun. Ringlets could be added to each side; sometimes these side curls were extensions that were attached to combs or headbands.

A close-fit bonnet was the head covering of choice during the 1840s. It was very closely fit, curving down around and past the face like a cone so that the wearer had no peripheral vision and no one could see the wearer’s profile—all part of the demure presentation. A pink bonnet lining might add a “glow” to the skin.

(A great timeline of women’s hairstyles from 1840 to 1890 can be viewed at https://vintagedancer.com/victorian/victorian-hairstyles-1840-1890/.)

The close-fitting leghorn bonnet was the head covering of choice

in the 1840s. (The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Stockings and shoes

Ballet flats were the norm, as were short boots with elasticized sides. Women wore knitted cotton or silk stockings in warm weather or wool stockings in colder weather. A length of ribbon or knitted garter held up stockings.

Accessories

Cashmere, paisley, or crocheted shawls were de rigueur. Gloves were proper anytime a woman left the house.

Outerwear

Capes with large collars were fashionable. Perelines, a short, shoulder-covering cape usually made to match the dress, were a common lightweight outerwear. Long mantles were also worn.

A tartan dress covered with a mid-length wool jacket. (1845, The V&A.)

1850-1860

In 1855, the daughter of an esteemed former captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club was seen playing on the St. Andrew’s links and was roundly criticized for it. In 1860, also at St. Andrews, a group of women trying to enjoy a few holes roughed out by caddies on abandoned land was publicly scolded and ordered to relinquish their golf clubs. Both instances, however discouraging, reveal that more and more women were playing golf, even on hallowed golf links.

While women golfers still did not have a specific outfit in the 1850s, female archers, swimmers, and horseback riders did. (1855, London Museum)

Dresses

Women's skirts were domed and bell-shaped during this period, supported by crinoline petticoats. Tiered skirts came into the fore; the flounces were often stiffened to stick out even more. Two-piece dresses became more common; in fact, women sometimes made two different bodices that went with a single skirt so that they could have long sleeves and high necklines for daytime wear and short sleeves and lower necklines for evening wear. The bodice would have a Basque waist that was elongated and fit over the join to the skirt.

There were other major style changes as well: women could choose to wear a short jacket like a men’s waistcoat, and blouses combined with skirts became more common under jackets. Feminine versions of men’s shirts, jackets, and vests were becoming more acceptable. Brocades and shot silks (which were iridescent and displayed two or more colors when viewed from different directions) became more popular, even in daytime clothing.

Two different styles of 1850s walking dresses. (Photo at left found on eBay; at right, The V&A.)

Undergarments

Up until this decade, women’s full skirts were supported by many layers of petticoats. By 1856, a single undergarment replaced the multiple underlayers: the crinoline. It was made of steel hoops or whalebone and unironically referred to as a cage. A single petticoat was worn on top of the crinoline so that its infrastructure didn’t show through the dress.

Also popular during this time were long bloomers and pantaloons trimmed with lace.

Hats/headgear/hair

The decorated bonnet was still very popular, but its brim shrank backward so that the front half of the head was visible, and the wearer’s peripheral vision was restored. Plusher hats made of velvet or silk started to come into play.

Hair was still parted in the middle, but side ringlets went out of style. Usually hair was pulled back in a tidy back bun or chignon. Bangs became a style option.

A selection of 1850s hats.

Stockings and shoes

Short leather booties with lace-up or button-up sides were common for out-of-doors. Alternately, a ballet-style slipper that laced up the ankle was for inside wear or fairer weather.

Black or white stockings were common, and these could be made of cotton or silk. Stockings could be plain or have small embroidered designs such as flowers. Still other women wore highly patterned and colored stockings that were really not for anyone else’s eyes but the wearer’s.

Accessories

Parasols were still popular and practical for protection from the sun, as were gloves. This was the period when cashmere shawls imported from India reached their peak popularity. Those with lesser incomes could get good quality imitations from manufacturers in the British Isles.

Outerwear

Tiered capes or jackets (called a carrick) were fashionable. A more masculine or military style, the coats were very practical in protecting the wearer from damp and cold. Sleeveless cloaks (called a pardessus) or mantles could easily be worn over voluminous dresses. Fringe trims were very popular.

After 1855, a loose jacket that fell straight from the shoulder with a wide sleeve appeared. It could be short like a bolero jacket or up to three-quarters length over the skirt, and it was usually very plain, with no trimmings.

An 1859 pardessus coat.

1860-1870

We’ve finally reached the decade when actual recorded history tells us what has long been suspected: there are a lot—a LOT—of women playing golf.

In 1867, the St. Andrews Ladies Golf Club was founded. They played on the Himalayas, an 18-hole putting green that still exists today. (The organization also still exists as The Ladies Putting Club of St. Andrews.) In 1868 at Westward Ho! in southeast England, a women’s course opened and hosted a medal competition. More and more towns and clubs took notice, and by 1890, more than 50 women’s golf clubs existed in the Great Britain.

This extraordinary 1868 photo of women playing on the Himalayas putting course at St. Andrews Old Course provides a wealth of information on fashion of the day.

(University of St. Andrews Archives.)

Dresses

The sewing machine had been invented in the 1840s, and by the 1860s, machines became more available. Not every garment had to be hand-sewn anymore. The invention of synthetic dyes also changed fashion. So brighter, fancier, and less expensive clothing became the norm. Queen Victoria’s devotion to Scotland also kept plaid and tartans popular.

Skirts were still voluminous in the first half of the decade. To make the skirt look even bigger, flounces and overskirts were added. Bodices were tight and buttoned up the front, but they no longer had to match the skirt. Necklines fit closely at the base of the neck. Sleeves were wide and flowing; some sleeves cinched up at the wrist.

After 1865, the skirt lost its bell shape at the front, and the extra mass moved toward the back of the skirt.

Skirts in the early 1860s were still large and bell-shaped. (Right: Philadelphia Museum of Art; left: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

By the end of the 1860s, the bell-shaped skirt had disappeared. Now the front of the skirt was flat. (Right: The V&A; left, WikiCommons.)

Undergarments

The large skirts that were worn at this time hid the hips, so corsets became shorter. Crinolines supported the skirt. After 1865, when the bell-shape went out of the front of the skirt, crinolines were made with half-hoops that created a flat front and a belled-out back. This led to the increasing popularity of the bustle in decades to come.

Hats/headgear/hair

All through the 1800s, the bonnet was the most popular head covering. But in the 1860s, a variety of much more stylish and much smaller hats emerged. These tied behind the head, usually around or through a chignon. Other head “coverings” were not hats in the conventional sense, but simply loose concoctions of lace, ribbons, flowers, and other trims. Later in the decade, hats tipped down over the forehead.

A net-covered chignon was kept loose to make the woman look like she had more hair. Sometimes braids that began above the ears were draped back into the chignon, which was often held together with a hairnet made of ribbon or crocheted yarn. These hairstyles exposed the ears.

Above, a simple 1860s hat. (Maggie May Clothing.) Below, a slightly wilder assortment.

Stockings and shoes

Stockings were available in many patterns and colors, and were held up with garters or ribbons. Button-up boots were also available in colors, although darker (leather) colors were most common.

Accessories

Parasol and shawls were still common accessories. Gloves were also considered proper for outside wear; these could be made of cloth or kid-skin. Crocheted or knitted gloves or mitts (fingerless gloves) also fit the bill for propriety and style.

Outerwear

Between 1859 and the mid-1860s, the Zouave jacket became very popular. This is a short jacket with an open front that cuts away from the waist. They were made of woolen fabrics and often had aspects of a military jacket, such as gold or black braid.

A paletot was a tailored coat fit neatly over an outfit, often made to match a specific dress. The coat would extend about halfway down the skirt and was as voluminous as needed to accommodate the skirt beneath. The coats were often trimmed out in fur, velvet, or other complementary material.

Shawls and capes were also still very common.

A paletot coat (left) and a fringed knit shawl (right), both common forms of outwear in the 1860s.

1870-1880

In the late 1870s, the age of Romanticism that began in the 1820s merged with the Aesthetic Movement, which believed in art for art’s sake and decried everything that was popular in the 1860s: the tightly corseted form, bright colors, and lavish dress. The motto for fashion in this movement was “beauty is simplicity and freedom.” Dresses of this time were free-flowing, with no corsets or other “dress improvers” underneath.

Aesthetic or artistic dresses. Note the (apparent) lack of corsetry and bustles. (Lily Absinthe.)

Dresses

Such free-spirited clothing was fine for the artistic set, but it didn’t offer quite enough decency for most women. Still, traces of the Aesthetic Movement crept into some mainstream fashion. A slender, fitted silhouette emerged in 1875 to 1883; it was a period referred to as natural form. The skirt narrowed during this time and the bustle was almost abandoned. Dresses could be made from cotton, linen, velvet, wool, or silk, and were slightly gathered at the waistline. The colors were soft and made from natural dyes. The skirts were draping, and bodices had large puffed sleeves.

Even so, fashion got even frothier. Most of the attention in a dress was on the back of the skirt: long trains, bustles, ruching, and ruffles appeared. Dresses were brightly colored or earth-toned, but all were extremely elaborate and covered with tucks, lace, bows, and ribbons. The skirt and tight bodice were separate pieces. Fitted sleeves could end at the wrist or elbow, and the neckline could be square, rounded, or V-shaped.

Skirt and blouse combos were also popular; the skirt would be belted at the waist.

An extremely elaborate walking dress from the early 1870s (left, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), and a much simpler walking dress from 1872 (The V&A).

Many sporting activities in addition to golf, including cycling, tennis, skating, swimming, and hiking, were becoming popular with women. Specialized outfits started to appear, but largely, women still had to make do with street wear. A small grace: ankle-length hemlines were more acceptable for walking dresses and other “recreational” outfits. The use of cotton fabrics allowed garments to be easily washed and dried.

Early 1870s lawn tennis. Men are dumbfounded.

Undergarments

For those who did not embrace the Aesthetic Movement, many different “dress improvers” and padded undergarments were still available to build the ideal feminine outline for the time: a long, sleek hourglass shape.

The full crinoline, in time, proved impractical for everyday life. Bustles, which rested on the back of the waist, took their place and were available in many different sizes and shapes. Other garments would have included a chemise, drawers, a petticoat, and tight corset.

Hats/headgear/hair

Hats of this period were famous for being tilted forward. Some hats were very small—really more than decorations than something that could protect you from the weather—but “picture hats” with wider brims became popular late in the decade.

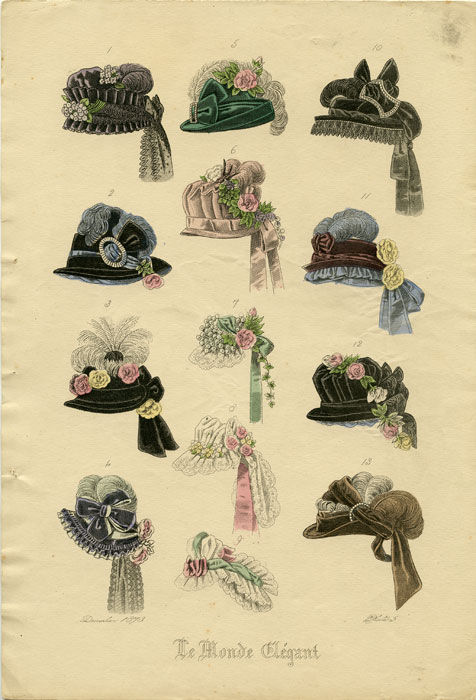

A fashion plate of 1873 hats from Le Monde Elegante (above). A straw boater would be more common for recreational activities (below).

Stockings and shoes

Over time, black or dark stockings became a practical choice for everyday wear, and white stockings would be reserved for fancier situations. But women also loved stockings with multi-colored patterns and embroidery, even though no one else was supposed to see them.

For outside wear, a lace-up walking boot or buttoned walking shoe were practical. The shoe had multiple straps that formed bars across the foot; sometimes there would be a bow at the toe. Both boots and shoes had a one- to two-inch heel.

.

Accessories

Jackets worn over the dress were common: some were boxy and about hip length, while others extended halfway or farther down the length of the skirt. More noticeable jewelry, such as earrings, lockets, neck ribbons, and bracelets, are worn. Gloves were worn for warmth and/or sun protection as well as for propriety.

Outerwear

The capes and shawls worn in earlier decades were not practical for active outdoor women. The newer bustle-style dresses worked better with jackets and coats. A knee-length, velvet-collared Chesterfield coat was fashionable, as was a caped overcoat called a caped ulster.

This fashion plate from 1878 shows a wide array of winter fashions.

1880-1890

Cycling, yachting, tennis, fencing, and golfing had become popular activities for well-heeled women, but more middle-class women were getting involved as well. Women’s sportswear began to appear, in particular, for cycling and fencing. Industrialization included the production of sports equipment, making it more affordable and accessible.

An 1880s silk tennis dress. (Powerhouse Museum)

A "sporting" dress. (The Met)

A ladies tennis association. (Lily Absinthe)

Dresses

The 1880s was a decade of what seems like the tightest, flounciest, most restrictive women’s clothing of the century. Tight corsets and very tightly fitting bodices, large bustles, high necklines, and narrow sleeves with protruding lace may have been fashionable, but their shackling effect may have set the course for dramatic change.

At the start of the decade, focus was on the back of the skirt: the bustle was concocted of many flounces, pleats, and trims. By 1885, the bustle had become so prominent that it protruded horizontally from the small of the back. But by the end of the decade, bustles had disappeared altogether, and dresses had a much slimmer fit from neck to floor.

Home sewing machines together with mass-produced cloth and trims were now available to all classes of women. Hems ended near the ankle.

Printed cotton gown with cuirass bodice and polonaise skirt.

(Circa 1883, The V&A.)

Undergarments

The distinctive silhouette of the early 1880s was that of a thin bodice and large skirts. To achieve this look, tight, metal-boned corsets and large, stiff bustles were necessary. They left little room for free movement—very emblematic of the status of women’s rights at the time.

Hats/headgear/hair

Bonnets covered with flowers were very popular, but these were usually reserved for more formal occasions. Large or small felt hats could be trimmed out with almost anything, but ostrich feathers were very fashionable. Bonnets adorned with feathers and broad satin ribbons were another daytime option. A flat-brimmed boater-style hat was becoming more popular for recreational pursuits.

For bonnets, hair could be braided and pulled into a chignon at the back of the head. Curled or waved hair would be visible at the front of the bonnet. Underneath a hat that sat on the top of the head could be tight, close curls pulled into a bun.

Stockings and shoes

The first female Wimbledon tennis champions in 1884 and 1887 gathered lots of public attention, and the first rubber-soled tennis shoes were produced around this time. Alas, the female golfer still had to rely on her street shoes.

Boots were still a very popular choice in the 1880s; normal colors were black, brown, white, and tan. But some styles could be very fancy and be decorated with embroidery and rich fabrics.

Accessories

Women of this decade used fans, parasols, handkerchiefs, and jackets. Jewelry continued to be very popular: it included large pins and brooches, earrings, necklaces, and lapel pins.

Outerwear

Waterproof jackets, which were tightly woven or felted, hooded garments, were practical outdoor wear. Double-breasted jackets and coats had high, straight collars that buttoned all the way to the neck. Their cut was narrow and fitted.

1890-1899

Everyday fashion started to shift away from stiff and decorative clothing at the start of the 1890s. Corsets and bustles made it difficult for women to move during daily activities, much less sports. As more and more women engaged in golf and other activities, they created sportswear out of their own wardrobes and out of necessity.

In 1893, the first Ladies Golf Union (LGU) was established. It promoted ladies golf and hosted its first championship that same year. A Miss M. Boys, a leading lady golfer of the late 19th century, described what female golfers should wear: “A neat sailor-hat, surmounting a head beautifully coiffured, every hair of which is in its place at the end of a round…a coat, a spotless linen collar and tie, and ordinary blouse and skirt, and a pair of well-made walking boots with water-repellent soles.”

A ladies' 1898 golfing outfit, displaying a club jacket. (The Met.)

Dresses

Female golfers wore free-flowing skirts and blouses with leg-o-mutton sleeves that were tight on the lower arm. Wide shoulders further accentuated the tight bodice and a small waist. Some women adopted masculine accessories such as a shirt collar and tie. Skirts ended at the ankle or several inches from the floor.

In 1890, artist Charles Dana Gibson created the fictional female heroine who became known as the Gibson Girl. She was bright, athletic, self-assured, and progressive, but she was still feminine. Her hour-glass shape—wide at the shoulder, small at the waist, and wide at the hips—became the ideal. She was regarded as “The New Woman”—independent and pursuing her own interests, which could have included an education, a career, or sports.

The Gibson Girl became the model of what was called The New Woman in the 1890s.

The two “uniforms” of The New Woman were the shirtwaist/skirt combo and the tailor-made suit. Shirtwaists were inexpensive and available in endless styles and materials; they were frequently white. Women often wore a tie with these shirts. The “tailermades” had a clean line: the skirts could be narrow or wide, and the matching jackets (usually neutral colors were favored) could be made in a variety of styles but were usually plain with wide lapels. A shirtwaist would be worn underneath. A New Woman-shaped sweater could also be worn for sports.

A shirtwaist/skirt combination (left, Kyoto Costume Institute), a tailormade suit (center, The V&A), and a walking suit (right; Nasjonallmuseet, Norway) of the 1890s.

Knit sweaters styled like a shirtwaist were ideal

for cooler weather. (The Met, 1895.)

Undergarments

The independent outer shell of The New Woman belied the amount of infrastructure beneath. The dramatic hour-glass silhouette was formed by a tightly laced, heavily boned corset. It was not a garment that was conducive to sports, or indeed, breathing.

A chemise and drawers underneath the corset completed the toilette.

Hats/headgear/hair

While many stylish hats were covered with flowers, taxidermied birds, feathers ribbons, and all sorts of other trims, women golfers usually wore plainer hats at the start of the decade and plain straw boaters near the end.

Hair was often worn in a large, loose, curled bun at the top or back of the head, in the style of the Gibson Girl.

A selection of 1890s hats.

Stockings and shoes

Rubber-soled tennis shoes—that is, shoes made specifically to wear for tennis—were available. These looked more like high-top, no-heeled boots, and perhaps some women golfers wore them. But any waterproof leather boot could have been worn.

As in previous years, stockings could be plain or colorful and patterned.

At right, rubberized tennis shoes (Wikipedia). At left, an 1892 rubber-soled boot.

Accessories

Parasols, umbrellas, and gloves would have been necessary for outdoor wear (gloves only for golf wear). Pockets had been sewn into women’s clothes since the mid-19th century, so it’s likely sporting clothing also had pockets.

Outerwear

The Myra Journal of Dress and Fashion, April 1, 1895, describes the ideal outfit for a lady golfer of the day, including outerwear. (The “colours” mentioned in the article refer to a usually red jacket worn by specific golf clubs to signify membership. The “sailor hat,” in this instance, refers to the flat-brimmed, ribbon-encircled straw boater hat that was ubiquitous among women golfers in the late 1800s and early 1900s):

“One has a brown serge skirt, with a double hem, which reaches only to the ankles. The full blouse is of buff covered cambric, with white spots, and is made with comfortable bishop sleeves, drawn into turn-back cuffs, a deep turn-down collar, with brown silk tie, and a draped silk wide waistband, sailor hat of buff straw with brown band. If particular colours are worn by the golf club, it is easy to have the dress made in such colours. A golfing costume like one from tennis or cricket, should allow plenty of room for freedom of action; the skirt and blouse form is, therefore, best. An extra coat or cape is a necessity. Many of the newest Golf capes are excessively neat looking; check tweeds are chiefly employed, and the linings in plaid silk harmonise with the colour of the tweed. A good make of cape is a covert coating, or box cloth, unlined; it has two capes, the upper one cut up the centre of the back; the collar is of velvet, edged with cloth, and the seams are strapped.”

The Himalayas putting green at St. Andrews, 1894. (University of St. Andrews Archives.)

The first four women in the first ladies championship in 1893, at Lytham St. Annes, UK, including winner Lady Margaret Scott (seated at right), who was considered very stylish as well as very cool player. (University of St. Andrews Archives.)

1890 ladies competition at St. Andrews. (University of St. Andrews Archives.)

Play at the Himalayas at St. Andrews, 1895. (University of St. Andrews Archives)

1899 and beyond

This is the start of the Edwardian period. Even though it’s outside of the featherie and gutty period defined in this article, we wanted to mention three very important developments.

1. Post-1900, the participation of women in golf—and in many other sports—skyrocketed.

2. Fashion became much more athletically friendly and practical for woman and men.

3. As actual sportswear became available, it often steered fashion even for women who did not participate in sports. The woman athlete pushed fashion forward because she had to. She adapted her own clothes, borrowed from a brother, and invented the clothing she needed to better enjoy her pursuits.

SOURCES (entries marked with * sell period clothing or patterns):

• “A Dress Historian Explains the Difference Between Stays and Corsets,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8tRK3gn-NA

• Beauty From Ashes, Adventures in Sewing: http://beauty4ashes7.blogspot.com/search/label/1814

• Family Search: https://www.familysearch.org/en/

• Fashion History Timeline, Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1870-1879/

• Glasgow Caledonian University, “Conventional to comfortable or respectable to practical: the evolution of women’s golf clothing in Britain, 1890-1935.” •https://researchonline.gcu.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/53832265/Costume_Article_FINAL.pdf

• History in the Making: https://www.historyinthemaking.org/womens-hats.html*

• Kate Kattersal Adventures: http://www.katetattersall.com/victorian-fashion-terms-n-z/

• Lily Absinthe Gowns and Corsetry: https://lilyabsinthe.com/*

• Maggie May Fashions: https://maggiemayfashions.com/*

• Mimi Matthews: https://www.mimimatthews.com/*

• Plaid Petticoats: http://plaidpetticoats.blogspot.com/p/research-compendium.html

• Sew Historically: https://www.sewhistorically.com/1840s-1850s-underwear-dressing-the-victorian-lady/

• The Dreamstress: https://thedreamstress.com/*

• Victoriana: http://www.victoriana.com/Fashion/womensgolfclothing.html*

• Victoria and Albert Museum (The V&A): http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1900-1970/

• Village Hat Shop: https://www.villagehatshop.com/content/50/history-of-hats.html*

• Vintage Dancer is an excellent site for finding ready-made clothing, but also on how to adapt modern clothing: https://vintagedancer.com/victorian/

• Vintage Fashion Guild: https://vintagefashionguild.org/fashion-history/the-history-of-womens-hats/

• What Should You Wear to Play Hickory Golf?

(The Hickory Hacker, YouTube) https://youtu.be/VBZz91ySQ_Y

Comentarios