Golf fashion for male golfers & spectators, 1800–1899

- cathylane1118

- Mar 11, 2023

- 32 min read

Updated: Mar 12, 2023

The following article and its sister, "Golf Fashion for Female Golfers and Spectators, 1800–1899," were inspired by a vlog created by Christian Williams, aka The Hickory Hacker, on what to wear when playing hickory golf. The lessons Christian has learned in his extensive historic golf experiences are extremely helpful. We suggest viewing the vlog first, then diving into this article.

This article covers 1800 to 1899. For our purposes, the featherie era ended with the introduction of the gutty ball in 1848, and the gutty era ended in 1899, when the Haskell ball was patented.

One of the most common questions people new to historic golf ask is, “What do I wear?” The answer is, of course, “It depends.” What decade or person do you want to emulate? What is your budget? Are you playing, watching, or perhaps helping at an event? What will the weather be like?

The goal in dressing for a featherie or gutty event is not simply to look “old-timey.” By wearing an era-appropriate outfit, you are making the event and experience better for yourself and others. You gain a better appreciation of history and (we hope) have more fun.

It’s unlikely that you will be able to find actual antique clothes that are in good enough shape to wear. Instead, look to companies that make historically appropriate clothing. Or, modify modern clothing using the visual cues outlined in this article. Tailors can be extremely helpful.

After the first few unpredictable decades of the 1800s, fashion for men was relatively consistent—sober and almost like a uniform. To help sort out the many options, we’ve tried to gather basic visual cues that you can use to kit yourself out in style, comfort, and historical accuracy.

Please consider the following while reading...

1. These are informed suggestions, not rules.

2. There would have been crossover between fashion eras: that is, people did not throw out their featherie-era golf clothing when the gutty ball happened along. But it’s probably best not to wear an 1800 outfit to an 1899 event. Ask your event host for what dates he or she is targeting.

3. This article suggests clothing that would be worn while playing or watching golf. Remember that featherie golf was largely a sport for the privileged, who had enough leisure time to play and money to afford “sporting clothes” and the equipment. The gutty era opened up golf to people of more modest incomes and wardrobes. But we can presuppose that people of all incomes were playing golf from 1800 to 1899.

4. Between 1800 and 1899, most golf in the world was being played in the British Isles, so that is where our fashion research resides as well.

5. Underneath your old-style outfit, go modern. We strongly recommend an under-layer of merino wool for cooler weather and sweat-wicking materials for warmer weather. Both will keep you more comfortable and protect the investment you are making in your outfit.

Men’s golf fashion: 1800-1810

The excavations of Pompeii and the Herculaneum in the 1700s had inspired a keen interest in Greek and Roman antiquity. While women’s fashions shifted to a draping, languorous style that revealed the body shape—very similar to white marble Roman or Grecian statuary—men’s fashions emphasized the male physique. Think of a statue of a Greek god.

This was right after the French Revolution: the fussy fabrics, laces, wigs, and plumes of the 18th century were now rejected. It was a new age of democracy in which soberness and uniformity in men’s dress were important factors, especially among businessmen. The Industrial Revolution was in full steam, which meant men spent much more time away from home, doing business with other men. Uniformity of dress publicly declared the new ideals of equality.

This dress outfit for the 1805 gentleman shows how revealing menswear was at the start of the century. Fashion was meant to emphasize the male physique.

Dress coats and waistcoats

Tailoring was key for men’s clothing. The physique was emphasized. Tail coats were cut in at the waist, either straight across or in an inverted U. Some were made of a fine, felted wool that could be cut with raw edges and molded to the body for an extremely personalized fit. Coats had high collars that sloped down to lapels cut with an M or V notch.

Waistcoats (or vests) were usually single-breasted and cut straight across at the waist. They had a stand collar and could be a solid color—sometimes the same color as the pants—or patterned. Waistcoats often provided the only color in a man’s outfit. Sometimes men would wear two waistcoats, possibly for warmth, style, and/or bulking up the chest.

Not everyone had resources for more than one waistcoat, of course. Most workingmen would have a vest, which they would sometimes wear with a white shirt made of inexpensive cotton and a tie made from a scarf or handkerchief. They would also have a (likely) wool coat, which could have been handed down and be much mended, so certainly not in the latest styles. A coat was necessary for warmth, but paired with trousers and a vest, this might form a man’s Sunday best, an outfit meant to last his lifetime.

An etching from 1800 shows how dressy menswear was at the time, even for sport. It's worth noting that while one person is wearing dress slippers and another is wearing high boots, the caddy has no shoes at all.

Shirts

Shirts were made of white cotton or linen and had a high stand collar. Some had a pleated or ruffled front.

Neckwear

Men wore cravats. A cravat is a large square of starched white muslin or silk, folded cornerwise again and again into a band, which could be tied in many different ways. (Consult YouTube for multiple videos on how to tie a cravat. Also see our article, “Men’s’ Neckwear, 1800–1899,” for additional guidance.) The way a man decided to tie his cravat was a crucial part of his toilette and a form of self-expression.

Another option was the stock, which was which was a pre-folded or pre-tied strip of white cloth, mounted on a solid strip that closes in the back with a buckle or a hook-and-eye. Sometimes stocks also had pre-tied bows attached to their fronts.

The 1806 etching at left and the 1804 painting at right show great disparity in social classes, but similitude in dress. Pantaloons, jacket, waistcoat, white shirt, tie, and hat were the order of the day. (Left, Brighton Public Libraries; right, State Hermitage Museum.)

Leg coverings

High-waisted pantaloons (longer pants) and breeches (fastened with buttons or ties right below the knee), both held up with braces, were popular. These were made from jersey or wool and were cut very close to the body, usually in a cream color that created a revealing, nude-like effect. Again, think about what a white marble Greek or Roman statue looks like. But these styles were also inspired by recent military events. Tucked into tall Wellington or Hessian boots and paired with clothing adorned with braid or tassels, the martial look was very common for the time.

Looser trousers were sometimes worn for informal situations or by working men.

Hat fashion for men was largely ruled by top hats and their variants

in the early 1800s. (Village Hat Shop)

Hats/hair

The top hat was dominant during this time, and there were many different styles of top hats. The working classes wore flat caps, which had been worn in Great Britain since the late 1500s. (For more on the history and various styles of flat caps, please see our blog, “The Ancient and Ubiquitous Flat Cap.”)

Men were either clean-shaven, or they might have the chin-strap beard, which connects long side-whiskers (what they were called before the term “sideburns” was coined) down the edges of the jaw and around the chin.

Hair was longish, tousled and/or curly.

Tall Hessian boots had curved tops, while Wellingtons had straight tops.

(Left, Wikipedia; right, LACMA.)

Stockings/shoes

Men wore tall Hessian boots, which had a curved top, or Wellington boots, which had a straight top. These were square-toed, long, and narrow at the start of 1800s. Dress pumps were also common. Working men wore work boots.

Stockings in the early 1800s were knee length or just over the knee and white (especially when worn with breeches), black, speckled, or striped. They grew shorter during the century.

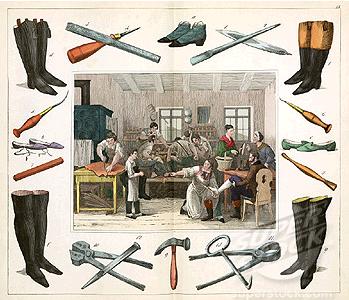

A hand-painted Spanish tile from 1800 showing a cobbler at work in breeches, vest, and shirtsleeves. Some cobblers, or cordwainers, produced featherie golf balls as a sideline.

Accessories

A gold pocket watch was a must-have for men who could afford them. The watch would be tucked into a waistcoat pocket and attached to a chain that draped across the waist and fastened to the waistcoat's front edge or to another pocket. Adorned with dangling seals, fobs, and winding key, the watch and chain remained part of the 19th-century male outfit for the entire century.

Other accessories that would be worn throughout the century include leather gloves and suspenders or braces. If a cravat or loose tie was worn, a non-showy stickpin might be used. A flask might be tucked into a pocket. Spectators would carry a cane or walking stick.

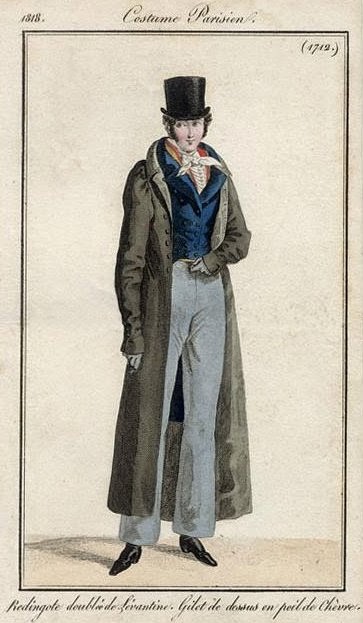

1800s men's greatcoat

Outerwear

The greatcoat was the style for the early 1800s. These were made of heavy milled cloth or tweed in black, dark blue, gray, or brown. These were much like a modern trench coat, but they were more fitted at the waist and had a flared skirt. These had high, sometimes velvet collars. The coats buttoned high as well, and the style of the overcoat generally mimicked the style of the clothing worn underneath. They extended past the knee; some nearly reached the floor.

Men also wore the carrick coat, which had one, two, or even three short cape layers over the shoulders. Full capes or cloaks were also an option.

1810–1820

Neo-classicism still influenced fashion, so garments that glorified the male physique were still in style. But other world events, such as the Napoleonic Wars, brought in styles from Prussia, Poland, and Russia, including the use of fur on clothing. Military touches such as braid, gold buttons, and tassels were also evident.

Trousers were becoming more popular in the 1810s for tradespeople and gentlemen.

Dress coats and waistcoats

By mid-decade, although tail coats were still prevalent, the frock coat was the new style for informal daywear. It had knee-length skirts that hung all along a fitted waist for a smooth and surrounding fit. These started out looking very military, but this effect disappeared by the end of the decade when they became the symbol of “middle class Victorian respectability.”

Wool dress coats were padded at the shoulder. Those who could afford it got a tailored fit to carry off the understated fashion.

A single- or double-breasted waistcoat, cut straight across at the waist, was worn underneath. Some were made of patterned materials, and some were intricately embroidered. The working man’s waistcoat was plainer and sometimes made of materials that could be laundered.

This excerpt from an 1813 painting by John Lewis Krimmel shows a town tavern scene that includes a range of tradespeople and their clothing. (Toledo Museum.)

Shirts

During this period, men’s shirts were white with a ruffled or pleated front. They had high, starched stand collars that reached up to the jawline.

Also new at this time was the detachable collar, which allowed one's collar to be highly starched while the body of the shirt could remain softer and more comfortable. Styles and shapes of these collars were myriad, which gave wearers many style options.

Neckwear

Men’s neckwear was very similar to that of the period from 1800–1810. (See the information above for reference.) Black and sometimes colored neckwear became more common. The knot, color, and fabric pattern a man selected were all ways to express himself.

The same basic outfit, but with adjustments to pattern and color. (Center credit: The Tate.)

Leg coverings

Men wore breeches or pantaloons, usually not the same color as the jacket, for daytime.

Crepe or silk jersey pantaloons were meant to cling to muscled legs. By the end of the decade, padded stockings might be worn to create the impression of more muscle mass.

Trousers are increasingly popular. These were not so tightly fitted at the calf and often had a strap around the instep to keep the pant’s legs taut.

Breeches, pantaloons, and trousers were very high-waisted so that the waistcoat generously overlapped them. This kept the shirt underneath from billowing out from in between, which would have been considered quite gauche as shirts were largely considered to be underclothing.

Hats/hair

Top hats in various sizes and colors were still the fashion for businessmen. The working classes wore flat caps.

Facial hair was beginning to come back in style. More men had side-whiskers, and some had small chin patches under the lower lip. Hair is a bit shorter than the previous decade.

Stockings/shoes

Men still tucked their pantaloons into tall Hessian or Wellington boots. Dress slippers or slip-on shoes were prevalent. Stockings in the early 1800s were knee length or longer and were white, black, speckled, or striped. They grew shorter during the century.

Accessories

Men wore tan, gray, or brown gloves for daytime. A pocket watch tucked into a waistcoat pocket and attached to a chain that draped across the midsection, was customary.

1812 greatcoat and 1818 carrick coat.

Outerwear

The greatcoat, carrick coat, and cloak were still worn. See the Outwear section for 1800–1810 for more guidance.

1820–1830

Between 1820 and 1825, the Neoclassical period ended and the age of Romanticism began. This was a time when people valued freedom of expression and emotion in art, literature, music, and fashion. The Romantic era, which lasted until 1840, basically reversed Neoclassic fashion. People were inspired by the aesthetics of older, even medieval times (although this was much more evident in women's clothing).

The male silhouette in the 1820s was very exaggerated, with a slim waist, broad shoulders exaggerated by puffed sleeves, and a wide hip.

Dress coats and waistcoats

The male silhouette changed during this time. The waistline of a coat was tightly nipped in, and sleeves were puffed at the shoulder. The collar was very high. A wide chest, narrow waist, and shapely legs were fashionable. Coats and stockings were sometimes padded for a more exaggerated effect. Younger men and sometimes military men even wore corsets in order to achieve an hourglass shape. Waistcoats were extravagant and made of materials such as a lady might have chosen for a dress. Some men wore two waistcoats to widen their chest girth. This dramatic silhouette lasted into the early 1830s.

Working men, of course, were little concerned with such niceties. But they likely also wore a frock coat or cutaway/tail coat, together with a single- or double-breasted waistcoat that had a shawl collar.

The desired shapely form of the 1820s man was sometimes helped along with padding in the jacket and stockings.

Shirts

A common shirt was white with a collar that extended above the chin, echoing the collar of the coat. Its front was pleated or had tucked panels for daytime wear. The neck openings of men’s shirts only went down about as far as mid-chest: they did not button all the way down the front.

Neckwear

Men’s neckwear was very similar to the period from 1800–1810. (See the information above for reference.) Black and sometimes colored neckwear became more common. A man’s selection of knot, color and fabric pattern were all a means of self-expression.

Men's trousers in the 1820s ranged from narrow to quite loose. (Left, Fashion Museum, Bath; center, V&A Museum.)

Leg coverings

High-waisted trousers, held up by braces, were more common by 1825. Some had a very narrow fit, reached just to the top of the shoe, and had a strap that fit over the instep to keep the legs taut. But other styles were loose from top to bottom. They could reach the ankle in length or stop a bit short of the ankle. They were often light in color, although they could also be darker or vertically striped.

Breeches were common with boots for sporting activities.

A workingman’s trousers or breeches would have been made from cotton or linen. They would have been dark in color or a natural, undyed color between white and tan. Nankeen was a very common fabric of the time. Durable and fine-textured, it is a pale yellowish cloth originally made in Nanking, China, from a yellow variety of cotton. It was so universally accepted for clothing use that later ordinary cotton was dyed that same color and generically called nankeen.

Hats and hairstyles of the Romantic period. (Village Hat Shop.)

Hats/hair

Top hats were still in style The working classes wore flat caps or tams.

Side-whiskers are still fashionable, as was the chin patch. Hair was wavy or curly, but with a distinct, deep side part and a bit more styling.

A cobbler's shop in early 1800s Belgium reveals workers wearing cotton shirts, waistcoats and trousers. Some cobblers, or cordwainers, produced featherie golf balls as a sideline.

Stockings/shoes

High boots were still around, but ankle boots and informal lace-up leather shoes were becoming more common. Some of these shorter boots had elastic gussets on the sides to keep them snug. Men also wore a slip-on leather shoes. All shoes had a pointed toe.

Stockings in the early 1800s were knee length or longer and were white, black, speckled or striped. They grew shorter during the century.

Accessories

Men wore tan, gray, or brown gloves for daytime. Pocket watches and chains were very common.

An 1820s frock coat that makes a real statement. (LACMA)

Outerwear

In addition to the greatcoat, carrick coat, and cloak, a heavier wool version of the frock coat was worn. It could be knee-length or longer, and it flared out at the waist.

1830–1840

Queen Victoria ascended to the British throne in 1837, marking the start of the Victorian era. Societal and fashion changes attributed to her reign don’t start until after her marriage to Albert in 1840, but the ball is in motion, rolling toward extreme propriety in manners and customs.

Of note in English history is the Great Reform Act of 1832, which extended the vote to men who were small-land owners, shop owners, and tenant farmers, among others. Of course, this didn’t erase the divide between upper and lower classes. But expanded suffrage rode alongside developments in fashion that democratized menswear, including the sack coat, which was invented in France in 1840.

The First Meeting of the North Berwick Golf Club, a painting created in 1835 by Sir Francis Grant, illustrates how similar yet how different caddie and gentleman clothing was. (Painting now hangs at The Links Club, New York.)

Dress coats and waistcoats

Romanticism was still in full dramatic blaze in the 1830s. Broad shoulders and hips, separated by a tiny waist, were stylish for men and women, so corsetry and padding were worn by most women and some men. The tailcoat was the style for a dress coat, while the frock coat was for daily wear. It was generally made from plain wool in dark colors.

The waistlines of jackets were still nipped in, and the coat’s skirt was flared out. There was a still a puff at the shoulder. But when the Romantic period ended in 1837, the extreme (and no doubt, uncomfortable and inconvenient) hourglass shaping of the male body disappeared.

The waistcoat provided color with rich patterns and fabrics. They generally had a rolled or shawl collar, and men might wear more than one.

An etching of an apple seller at work in the 1830s shows that the outfits of tradesmen were not all that different from those of gentlemen, but their clothes were probably made from lesser quality materials.

Among workingmen, a variety of coats and matching waistcoats are worn. For economy, sometimes a man’s pants were made from the same fabric as his coat and vest. All garments were mostly plain and functional, and they would be protected at work by aprons, gaiters, and other outerwear.

Shirts

Shirts were white with tall, straight collars. They often had pleated tucks on the front—the only part seen through the waistcoat and coat—and the rest of the shirt was plain.

Both tail coats (left, Kyoto Costume Institute) and frock coats (right, V&A Museum) could be customized with waistcoats and cravats for very different looks.

Neckwear

The high-collared jackets popular at this time hid large and complicated cravats. So new styles of neckwear started to emerge: the bow tie; scarves and neckerchiefs (more associated with working classes); the ascot; and the four-in-hand or long tie. Some cravats were more like a tube with no bow or knot in front—like the neck of a turtleneck—while others were tied in some version of a bow. Neckwear switched from white to black or colors for daywear.

Detachable collars were also available in a wide range of styles, which gave wearers even more options.

During this period, pants had a button-up, drop-panel fronts, but some styles were using a center fly front instead. The pants on the left are made of nankeen, a very common fabric of the time. Durable and fine-textured, it is a pale yellowish cloth originally made in Nanking, China, from a yellow variety of cotton.

Leg coverings

Trousers were fuller in the leg for daytime wear and were usually lighter in color than the coat. More narrowly fitted pants had an instep strap for tautness. Light-colored pantaloons or knee breeches with tall Hessian boots were also still worn.

Hats/hair

The top hat still reigned for business wear. The working classes wore flat caps, although the gentry had also adopted this style for sporting or country wear.

The chin-strap beard is seen again, sometimes with a mustache or chin patch. Hair is a bit longer, but still parted, combed, and styled.

Stockings/shoes

By the mid-1830s, short boots with elastic gussets were popular. Some short boots were laced in front, and both of these styles remained until the end of the century.

When men began wearing trousers more than breeches, stockings became shorter. They were usually black or white, made of cotton or wool.

Accessories

As before, men wore tan, gray, or brown gloves for daytime, plus a pocket watch and chain. Embroidered braces were in fashion; these would often be a gift from a mother, fiancé, or wife.

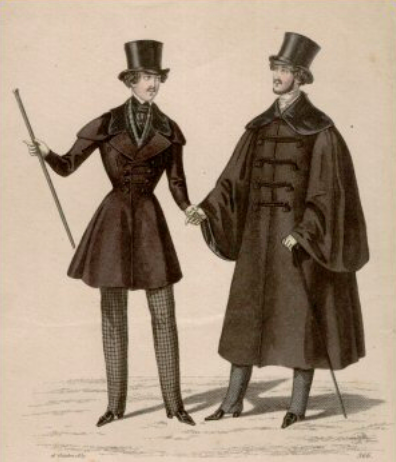

1836 and 1837 samples of men's outerwear. At left is a frock coat and cloak; at right is a frock coat and tail coat.

Outerwear

In addition to the greatcoat, carrick coat, and cloak, a heavier wool version of the frock coat was worn. It only extended to about the knee.

1840–1850

The sewing machine had been invented by the 1840s. These machines basically industrialized the production of ready-to-wear clothing. Shirts, neckwear, coats, and pants were now more readily available to all men, not just those who could afford a tailor.

Queen Victoria had a new royal residence in Scotland, so tartans were very popular. Sir Walter Scott’s novels, which were set in Scotland, also drove the craze of all things plaid and Scottish. Tartans continued to be in style into the 1860s.

Charles Lee's 1847 painting The Golfers is a treasure-trove of information about 1840s men's fashion. Amid the fancy red club coats are tail coats, frock coats, and the newest arrival at the party, the sack coat. All manner of neckwear and headwear is visible.

Dress coats and waistcoats

In the 1840’s menswear, the hourglass shape of the 1830s gave way to a more understated look that favored a long, narrow, fitted line. The waistlines of jackets dropped, sleeves narrowed, and shoulders smoothed out.

The black or dark wool frock coat was still standard daywear, a fact that continued to the end of the century. But when the sack or sacque coat was invented in France in the early 1840s, and there was no stopping its popularity among the working classes, business classes, and upper classes. Comfortable and loose-fitting, they were ideal for all manner of pursuits, including golf. They could be made from linen, cotton canvas, tweed, or wool, in almost any color or pattern. A sack suit with matching jacket, trousers, and vest was called a ditto.

(For more on the sack jacket, please see, “The Sack Jacket, the Great Equalizer.”)

The 1840s was a transitional time for men's fashion. At left is a Charles Lee study of caddie Sandy Pirrie, drawn for his painting The Golfers. Pirrie is shown in an older style: tail coat, cream-colored pants and waistcoat, and a high color and cravat. The sack suit at right is an example of a ditto—a three-piece suit made of the same fabric—a much more modern look. (Left: National Galleries of Scotland; right, Fashion Institute of Technology.)

Waistcoats or vests could be single or double-breasted; they had a deep V-front, with two or three pockets. Fancier outfits featured colorful patterned silks and embroidery; working-class versions were made from basic cottons, wool, or tweed. Buckles replaced ties on the back of some vests.

Waistcoats in the 1840s could be very elaborate. (Left: Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture; right, Wikicommons.)

Shirts

Men wore white shirts with starched and turned-up or folded-over collars.

Neckwear

White neckwear was now reserved for evening wear, while black or colored/patterned neckwear was common for daytime. Collars were upstanding, usually with the front tips folded down. The neckband was narrower, but the bow or knot was very large. A scarf could be knotted loosely and fitted into the top opening of the waistcoat and fixed with a pin. Very large, flat, and horizontal bow ties were popular.

Etchings of a London street shoe seller and a cobbler's shop, both from the 1840s, provides a glimpse of how tradesmen would have dressed.

Leg coverings

Up until this point, most men’s pants had a button-up, drop panel front, but now the center fly front becomes prevalent. Trousers were common and more full. Knee breeches and tight pantaloons were still worn for country or sporting wear. The stirrup that went over the foot instep disappears in this decade.

Pants often did not match jackets and could be light-colored, tweed, or plaid. As part of a sack suit, they could be made from checked, striped, or darker solid colors. Workmen wore sturdy cotton work pants and boots.

A sampling of hat and hairstyles for the 1840s through the 1870s. (Village Hat Shop.)

Hats/hair

Men still opted for the silk top hat. For “sporting tweeds,” they might choose a wide dark brown or black felt hat called a wide-awake. (It’s the same hat the Quaker Oats man wears.) Of course, the flat cap was always in style.

Men had ear-length or shorter hair, parted on one side. They had many options for facial hair: clean-shaven, full beard with mustache and/or side-whiskers was common, as was long side-whiskers with a small mustache and/or chin patch.

Stockings/shoes

Men still wore short boots with elastic gussets. Short, lace-up boots and slip-on or tie shoes were also in style.

When men began wearing trousers instead of breeches, stockings became shorter. They were usually black or white, made of cotton or wool.

Bow ties in the 1840s could be comically large. (Los Angeles County of Museum of Art.)

Accessories

Embroidered or plain braces, gloves, and a watch and chain were still part of a man’s everyday outfit.

Outerwear

Skirted greatcoats were still common; these could be single- or double-breasted. Carricks and capes were worn. The paletot, a tailored but relaxed men’s overcoat that came to the knee, was popular. Oversized frock coats with a looser fit were also worn.

1850–1860

This was a time of great events in golf. The more affordable gutty ball was introduced in 1848, making golf possible for everyone, not just the "well-feathered" rich. In April 1851, Young Tommy was born, and in July of the same year, Old Tom headed to Prestwick to design a new links course. In 1852, the railway came to St. Andrews, and with it came throngs of golfers and golf fans. This spurred the construction of the R&A Clubhouse at the Old Course in St. Andrews in 1854. Things were never, ever going to be the same.

More and more people were golfing, both men and women. For the most part, golfers played in street clothes. Ready-made clothing was even more available and affordable. The invention of aniline dyes in 1856 started a trend toward more vivid and garish colors. Patterns in men’s clothing really went over the top in some cases, with full suits of plaids, stripes or checks.

Sack coats dominate this photo of golfers at St. Andrews in the 1850s. Tom Morris, Sr. is at the far left; Daw Anderson is at center, carrying clubs; and Allan Robertson is third from right.

(St. Andrews University Archives.)

Dress coats and waistcoats

The silhouette of men’s fashion remained narrow with close-cut sleeves and trousers. By mid-decade, styles began to relax. Sleeves were broader and the waistline rose. Jackets lengthened into longer, straighter cuts.

For sporting, work, and general daytime wear, the sack jacket was very popular. Cut straight with small lapels, and often with three patch pockets on the outside, it had a comfortable and relaxed feel. A sack jacket buttoned high to the neck. It was usually made in dark colors, but patterns, lighter tweeds, canvases, and linens were also worn. Coats and trousers could be different colors and fabrics, or both pieces and even a vest could be cut from the same cloth. It’s easy to see that sack suits were the progenitors of the modern business suit.

Samples of 1850s waistcoats. (Left and center, V&A Museum; right, John Bright Collection.)

Waistcoats/vests could be colorful and fancy, but for the working man, they usually matched a utilitarian jacket.

Frock coats were still being worn. In the 1850s, the coat’s fastening rose higher, which shortened the lapels, while the waistline lowered. The double-notched M lapel went out of fashion this decade. Sleeves were now wider at the shoulder and tapered toward the wrist.

Shirts

Shirts were white with separate or attached collars, which weren’t as tall as in previous decades. Softer, turned-down collars were also common.

Neckwear

While a cravat/stickpin combo or a large bow tie were still popular choices, the long, vertical tie had become popular attire, especially for leisure/sporting activities. These ties were practical because they stayed in place and didn’t restrict movement. Bow ties became smaller by the end of the decade.

Cravats were eventually replaced by thin silk neckties, sometimes tied into a flat bow. Sometimes bows had jaunty, asymmetrical ends. Ties could have paisleys and other patterns in jewel colors, but usually they were simply a dark color or black.

Leg coverings

Trousers either had a straight cut with tubular legs or were loose at the hips and tapered at the ankles. A new invention, the front crease, was introduced in more stylish circles. Pants had a fly front and could be made of plain material or be striped, checkered, or plaid. However, black trousers were becoming more common by the end of the decade.

Men's suits during the 1850s could be very somber or quite flamboyant. (Left, LACMA; center, Wikicommons; Right, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Hats/hair

The top hat was still about, but for daily wear, the domed bowler caught on. Whether gentleman or working man, the flat cap was always great for golf.

Men’s hair was worn tidily combed and parted on the side. The decade marked the return of the beard, thanks to the Crimean War (1854–1856). British army soldiers were not allowed to have beards until the war, when freezing temperatures made it impossible to shave with soap and water. When these soldiers returned home, beards were the hallmark of a war hero, and soon all men started to grow beards.

Beards were accompanied by long and bushy side-whiskers whose shape resembled mutton chops, from which this style gained its name. Wearing mutton-chops with just a mustache was a style that Prince Albert adopted, and many men followed his example.

The servants of Major Hugh Lyons Playfair are curiously posed for a calotype (an early form of photography) at his front door in St. Andrews in 1850. The men are dressed the same as any golf professional of the day. The multi-talented Playfair may have taken this image himself as he was an enthusiast and a member of the Edinburgh Calotype Club.

(National Libraries of Scotland)

Stockings/shoes

Short boots or low slip-on shoes were still what most men wore. After 1850, tall boots disappeared except for riding or other sports. Working men wore work boots.

Spiked golf shoes are mentioned in the 1857 issue of The Golfer’s Manual, one of the earliest known references to specialized golf shoes.

Stockings were usually knee-high and usually dark, made from cotton or wool.

Accessories

Braces, gloves, gaiters, and a watch and chain are common accessories.

An 1862 carté-de-visite photo of the Prince of Wales (right) and Prince Louis of Hesse. Both men are wearing Chesterfield coats.

Outerwear

Short cloaks, capes, and a heavier outdoor version of the sack jacket were common outerwear options for men. The Chesterfield, which had no waist seam and hung looser than a frock coat, became fashionable. In the 1850s, it had some shaping at the waist, but this disappeared in the 1860s. A Chesterfield could be single- or double-breasted.

1860–1870

In 1860, the first Open Championship was held at Prestwick. Between 1860 and 1870, either Tom or Tommy Morris won the Open seven times between them. The luminaries of golf were emerging, and many hundreds and eventually thousands of admirers took note.

Men’s clothes at this time were largely mass-produced and had an oversized appearance. Synthetic dyes introduced in the late 1850s made bright colors all the rage in 1860s fashion.

Sack jackets predominate in this photo of professionals at Westward Ho! in 1860. But check out the the wide range of hats. Young bucks in the front row (left to right) are Young Tommy Morris, Bob Kirk, and John Allan.

Dress coats and waistcoats

Many men wore loose-cut, somewhat shapeless sack jackets and wide tubular trousers. They buttoned close to the neck. It was fashionable for men's coats and jackets to be single-breasted and semi-fitted, extending to mid-thigh. By late 1860s, the overall silhouette had slimmed down and jackets were made straighter and shorter, a trend that continued into the 1870s.

The frock coat was still prevalent, but was becoming less popular with younger men. Most menswear continued to be in dark and light neutral colors; a dark jacket would commonly be worn with lighter pants. Three-piece suits were very popular.

Sack jackets were often worn with a matching waistcoat. Waistcoats were single-breasted and had either a shawl collar or no collar at all.

The sack coat and suit were amazingly versatile. They could be quite sober or a real personal statement. (Left to right: 1863, Wikicommons; 1867, Willie Park, Sr., Wikicommons; 1860s, Fashion Institute of Technology; 1860s LACMA.)

Shirts

Shirts were more plain than ever as they weren’t visible under high-buttoned jackets. Collars were not as high and often were folded over.

Neckwear

Cravats were now made from a narrow band of fabric, usually less than one inch wide. These were tied in front as a small, flat bow, or knotted (usually four-in-hand) and fixed with a pin. Longer neckties were also popular. Neckwear could be patterned or colored.

Leg coverings

Trousers were loose down the leg, tapering to the ankle. Made in light or dark colors, patterns became less common through the decade. Pants were high-waisted, loose at the waist, and held up with braces (suspenders), which sometimes were embroidered.

Knickerbockers, or knickers, a loose form of tweed breeches that fastened below the knee with buttons or buckles, were adopted for golf around this time, usually worn with a Norfolk or other sports jacket (so named because they were jackets worn when playing sports—today, sports jacket generically refers to any casual jacket). They were cut three inches wider in the leg and two inches longer than normal breeches, which gave them a billowy look at the bottom. (These should not be confused with plus-twos or plus-fours, which were not popular in golf until the 1920s.)

Hats/hair

Hair is ear-level, neatly parted, wavy, and combed to the side.

Facial hair was definitely a means of self-expression at this time. Trim beards and mustaches and long mutton-chop sideburns (now named after Major General Ambrose Burnside, a Civil War hero who had an admirable set that connected to his mustache).

Another style was known as “Dundreary whiskers” or “Piccadilly weepers.” These were long and/or bushy side-whiskers worn with a full beard and drooping mustache. Dundreary whiskers were named after a fop in the play “Our American Cousin,” who had this style of facial hair. The Piccadilly name was used mainly in England, where dandies wearing this style were often seen in London’s Piccadilly Circus.

Top hats were reserved for formal wear by the end of the decade. Bowler hats, flat caps, and even flat-crowned straw hats were worn on the links.

Stockings/shoes

Short boots were common, with front-lacing varieties being very common. Lower shoes were also becoming more widespread.

The stocking industry went from a cottage industry to a factory environment with the 1864 patent of William Cotton's rotary or circular frame. His invention could produce elasticized fabric for socks 100 percent faster than previous methods. This increased color and pattern options, plus reduced costs to consumers.

Knickerbocker stockings were worn with knickers. They were often ribbed and had their tops turned down over a garter.

Accessories

A man’s accessories still included gloves and watch and chain.

A tail coat, Inverness cloak, and Chesterfield coat were all outerwear options at this time.

Outerwear

Overcoats of the time had a wide, shaped sleeve. A Chesterfield coat that was edged with braid and went past the knee was fashionable, as was a short, double-breasted reefer coat. Heavier versions of sack jackets were also worn. The Inverness cloak, which did not have sleeves and instead had a short outer cape to protect the wearer’s arms, was another option.

1870–1880

Luminaries like Young Tom Morris, Bob Kirk, Davie Strath, Willie Park, Jr., Jamie Anderson, and others were writing golf history. They were not men born of privilege and wealth, but were trendsetters just the same. They were young gentlemen, members of the Rose Club who dressed neither in red club coats nor as caddies. Their game and sartorial sense were on point.

This 1870 photo of Young Tom Morris has it all: an elegantly tailored morning jacket and waistcoat, the understated four-in-one tie and stickpin; watch chain with single, tasteful fob, and subtly striped pants topped off with an amazing belt.

Dress coats and waistcoats

This was a time of very somber men’s fashion. Coats and jackets were semi-fitted , more streamlined, less boxy, and thigh-length. Jackets and waistcoats were buttoned high on the chest, while shirt collars were stiff and upstanding, with the tips turned down into wings.

Men wore three-piece suits in dark colors, topped either with a sack jacket or a frock coat. For more formal occasions, a fitted frock coat or morning coat was appropriate. The sack suit was very popular, especially among working-class men.

During the 1870s, the deep V opening in the vest reappears, mainly in the double-breasted variety. But on the single-breasted vest, the fastening was higher, and the collar and lapels were smaller.

Old Tom Morris and Young Tommy Morris are wearing the same basic suit in 1875, but with completely different style. Note the differences in the lapels: Tommy may be wearing a double-breasted jacket, while Old Tom's coat is single-breasted.

(University of St. Andrew Archives.)

Shirts

Men’s shirts were white, plain, and crisp. They could be worn with a turned-down collar or a high collar with the front tips winged down. Collar heights were going up again.

This collage of the 1870s members of the Rose Club shows a wide variety of hair and neckwear styles. (University of St. Andrews Archives.)

Neckwear

Mass-produced collars and neckwear greatly increased a man’s options. The four-in-hand tie (the same style knot used today throughout the Western world), bow ties, and ascots with stickpin were becoming more popular.

Leg coverings

Trousers remained very little changed for the rest of the century. For the 1870s, they were equal width at the knee and ankle, and they were cut a bit fuller for daywear. They were loose at the waist and held up with braces.

Knickers continued to be worn for sporting and country wear.

A sampling of hair and hat styles for 1870 to 1880. (Village Hat Shop.)

Hats/hair

As the final accessories for their outfits, men often wore bowler hats, straw boaters, and flat caps, all of which suited the sack suit very well.

Hair was worn shorter than previously and parted at the center or side. Most men had side whiskers and trim mustaches. Facial hair was kept more trimmed. Some younger men were now sporting only a mustache.

Stockings/shoes

Shoes and short boots were square-toed with low heels. It’s worth noting that by the late 1870s, specialized rubber and canvas shoes were being made for tennis: sportswear was beginning to emerge.

Socks were calf- to knee-high in length and available in a wide range of styles and colors.

Accessories

A man’s accessories still included gloves and watch and chain.

A wide variety of jacket, tie, hat and hair styles from the 1870s.

(Left to right: V&A Museum, The Royal Trust, Wikicommons.)

Outerwear

The Chesterfield coat, Inverness coat, Ulster coat, Inverness cape, or rubberized Macintosh were all in circulation at this time. Most of these were mid-calf or knee-length. A heavier version of the sack coat worked as an overcoat as well. For sporting, some men wore a double-breasted reefer jacket.

1880–1890

As golf spread throughout the United Kingdom and then on to the British Empire and the United States, manufacturers took note. The prescience of craftsmen-clubmakers like Robert Forgan, George Nicholl, and James Gourlay to move into mass production—or to partner with those who could—was admirable.

The ready-to-wear garment industry grew dramatically, which enabled any man to look respectable at an affordable price.

Old Tom Morris takes the seat of honor at the center of this photo from the 1880 Open in Musselburgh. He and his companions are all wearing the same style of jacket, but they have all kitted themselves out in very different ways.

Dress coats and waistcoats

The sack suit continued to reign, with its relaxed fit, versatility, and reasonable cost. It could be double- or single-breasted, very casual or more formal. The fashion became so acceptable in the Western world that a dress version of the sack jacket emerged. Worn with a white shirt and a black or white tie, it became known as a dinner jacket in the UK or as a tuxedo coat in the US.

Blazers became popular with rowing, tennis, and cricket enthusiasts. These were single-breasted and often worn with light flannel trousers. The Norfolk jacket was also a popular sporting costume, usually paired with knickers and gaiters. The frock coat was still a fashion staple, as was the morning coat.

Jackets were buttoned high, so fancy waistcoats were less important. Vests were often made from the same fabric as a suit’s jackets and trousers.

This photo of Old Tom, Peter Brodie, and James Whitecross possibly at North Berwick is a study of the dress of older golfers in 1880. It's likely that there are bow ties hiding beneath those beards. (University of St. Andrews Archives.)

Shirts

White shirts were still common, but colored or vertically striped shirts were also becoming acceptable, especially for country or sporting wear. Tall, stiffened collars continued to grow in height into the 1890s. Their tips were winged down. The workingman favored a turned-down collar.

Neckwear

The bow tie or four-in-hand tie were popular. The string tie and ascot were also still in the running. Jackets were buttoned high, leaving little room for neckwear, so ties shrank in size.

Formal interpretations of the three predominant jackets of the day: the sack coat, the morning coat, and the frock coat. (1882, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Leg coverings

Some trousers patterned in plaids or checks were worn with dark coats. Loose knickers and gaiters were sometimes worn for sports.

A sampling of hats and hairstyles from 1880 to 1890. (Village Hat Shop)

Hats/hair

Bowler hats, top hats, and flat caps remained popular. The straw boater was first worn for tennis and rowing, but it also was becoming more acceptable in everyday life. A deerstalker hat, which was a tweed cap with a brim in front and in back, plus ear flaps that could be tied under the chin or on top of the head (think Sherlock Holmes), came into use, as did the homburg (think Winston Churchill). The cricket cap is adopted by golfers at this time: this is a felt, skullcap-like hat with a very short bill.

Younger and more fashionable men were getting rid of all of their facial hair or wore just wearing a mustache. Beards and sideburns became the style of older and more conservative men.

A selection of men's socks from 1883.

Stockings/shoes

Short boots and slip-on shoes were worn. The toes were more rounded in the 1880s.

Socks were calf- to knee-high and could be made of wool or cotton. By this point, men’s socks were available in a wide array of patterns and colors.

Accessories

A man’s accessories still included gloves and a watch and chain.

An 1886 photo from Westward Ho! is interesting because of the wide range of ages, outfits, and hats that are represented. (University of St. Andrews Archives)

Outerwear

The Chesterfield coat, Inverness coat, Ulster coat, Inverness cape, or rubberized Macintosh were all in circulation at this time. Most of these were mid-calf or knee-length. A shorter version of the Chesterfield appeared; it stopped at the knee. A heavier version of the sack coat worked as an overcoat as well. For sporting, some men wore a double-breasted reefer jacket.

Coats were generally made of heavy milled cloth or tweeds in black, dark blue, gray, or brown.

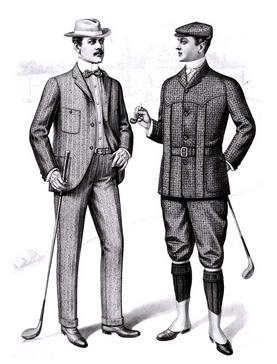

1890–1899

The “Gay Nineties” were a period of transition from the stiffness and rule-driven ways of the Victorian era to a time of more societal freedom, especially for women. Sports such as golf, cycling, and tennis offered opportunities for men and women to socialize and stay fit. New technologies, including the introduction of electricity in clothing manufacturing, further expanded the ready-to-wear market. Men had more and more wardrobe options.

The uniformity of hats and facial hair in this 1897 photo of Monifieth Club players is remarkable. Flat caps rule, as do mustaches. The majority of men are wearing the four-in-hand long tie, although there are a few with no tie at all.

Dress coats and waistcoats

As in the 1880s, men’s fashion had a narrow silhouette. Three-piece tweed or canvas suits were common. Frock coats were still worn, especially in more formal situations or by older or more conservative men. The morning coat could be made informal as part of a three-piece tweed or plaid suit or very formal when paired with dark trousers, white shirt, and white or patterned tie.

Waistcoats were often made of the same material as a man’s jacket and pants, but they could also be made of a lighter, darker, or neutral fabric.

Much more sportswear was available for activities like visiting the seaside, yachting, and tennis. Relaxed clothing was worn for golf. For example, a pleated, tweed Norfolk jacket with adjustable belt, worn with loose breeches or trousers, was socially appropriate and comfortable. A sack jacket with matching trousers and no vest was equally acceptable.

Knitted or crocheted garments had been around since the 15th century, but in the 1890s, they were adopted by athletes and called a sweater (because they caused you to sweat, which was considered healthy) in the US or a jumper in the UK (from the French word jupe, meaning a short coat). More flexible than a jacket, sweaters quickly caught on as golf wear.

Common golf outfits of the 1890s. (Left, date not specified, Wikicommons; right, 1898, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Shirts

Men wore heavily starched shirts with stiff stand or turned-down collars and sometimes matching cuffs. Shirts and waistcoats could be more colorful. This decade is known for the tallest collars of the late 1800s: some were 3 inches in height.

Neckwear

A mix of high collars and folded-over collars was worn. The long tie with the four-in-hand knot reigned supreme. But the bow tie, ascot, and knotted scarf were also frequently worn.

Dr. Miller and Dr. Steggall at Machrihanish in the 1890s (onlooker unknown).

(University of St. Andrews Library and Museum)

Leg coverings

Trousers were more relaxed in cut. They were more narrow and creased down the front and back. Trousers and loose breeches were often made of vertically striped or plaid fabrics.

Hats/hair

Bowlers, fedoras, homburgs, and flat caps were all very common. Hair was short, tidy, and parted on the side.

Being clean-shaven was once again in style, especially for younger men. By 1900, almost all men were done with facial hair for several unpleasant reasons. At the turn of the century, the three leading causes of death were pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrhea/enteritis, and many people believed that facial hair spread germs. Second, the Gillette company invented the disposable razor blade in 1895, which made shaving easier, faster, and cheaper. It also made shaving safer because, previously, a man could inadvertently give himself lockjaw with a cut from an unclean straight razor.

A sampling of hat and hair styles from 1890 to 1900. (Village Hat Shop.)

Stockings/shoes

Men wore short boots that buttoned or tied in front. Slip-on leather shoes were also common, as was a tie shoe that greatly resembles the modern oxford. The toe of footwear became pointed in the 1890s.

Socks were calf- to knee-high and could be made of wool or cotton. By this point, men’s socks were available in many colors, styles, and patterns.

Accessories

A man’s accessories still included gloves and watch and chain.

Outerwear

The Chesterfield coat, Inverness coat, Ulster coat, Inverness cape, or rubberized Macintosh were all still in circulation at this time. Most of these were mid-calf or knee-length, but some ended between the calf and ankle.

Old Daw (David Anderson, at center) and his ginger beer cart with P. C. Anderson (seated) and Walter Egan on the Old Course at St. Andrews in 1900. (University of St. Andrews Archives.)

Beyond 1900

This was the start of the Edwardian period. Golf was exploding in popularity, as was golf fashion.

A few notes on menswear that distinguish this new century from the last.

• Neither breeches nor knickerbockers/knickers were new inventions: both were worn prior to and during the 1800s. However, blousy plus-twos and plus-fours were introduced in the 1920s. Edward, Prince of Wales, wore them during a visit to the US in 1924, and they became very common golf wear until the end of the modern hickory era in about 1930.

So if you want to be era-accurate for 1800–1899 play, slim knickers or breeches or breeks are appropriate. Plus-twos and plus-fours are not.

For definition:

—Properly fitted breeches or breeks end just over the knee (just long enough to allow the knee to bend without the garment riding up), are cut close to the leg, and provide the neatest, trimmest fit.

—Properly fitted knickers will hang 2 inches below the knee when unfastened and are cut a bit wider than breeches for a loose fit.

—Properly fitted plus-twos will hang 4 inches below the knee when unfastened and are cut a bit wider than knickers for a baggy fit.

—Properly fitted plus-fours will end 8 inches below the wearer’s knee when unfastened and are cut wider for the baggiest fit.

• Historians say that argyle socks were designed by Scottish clansmen in the 16th century when they applied their traditional tartans to foot coverings. Argyle patterning is actually just a tartan pattern turned so the squares become diamonds. (Try it!) Turning the woven tartan in that way allows the wearer/user to stretch the cloth on the bias, creating an elastic effect that’s pretty useful with socks.

Argyle socks and sweaters did not become fashionable for golf or everyday wear in the UK or US until after WWI, which ended in 1918. Again, we have to credit Edward, Prince of Wales. He helped popularize the patterned garments when he paired argyle sweaters and long argyle socks for golf. So argyles are not part of the featherie or gutty era.

SOURCES (entries marked with * sell period clothing or patterns):

• Family Search: https://www.familysearch.org/en/

• Fashion History Timeline, Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/ (1800–1890)

• Five Minute History: https://fiveminutehistory.com/five-minute-guide-waistcoats/

• Historical Emporium: historicalemporium.com/*

• History in the Making: https://www.historyinthemaking.org/library.html#18th-century

• Keikari: https://www.keikari.com/english/a-history-of-the-sack-cut/

• Maggie May Fashions: https://maggiemayfashions.com/*

• Mimi Matthews: https://www.mimimatthews.com/2016/10/03/a-century-of-sartorial-style-a-visual-guide-to-19th-century-menswear/*

• Pilfering Apples Tumblr: https://pilferingapples.tumblr.com/post/115413933346/mens-fashion-ca-1830-the-bottom-layers

• St. Andrews University Library and Collections

• The Dreamstress: https://thedreamstress.com/*

• Victoriana: http://www.victoriana.com/*

• Victoria and Albert Museum: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1900-1970/ and vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1840-1900/

• Village Hat Shop: https://www.villagehatshop.com/content/50/history-of-hats.html

• Vintage Dancer: https://vintagedancer.com/victorian/victorian-mens-fashion-history/

• Vintage Fashion Guild: https://vintagefashionguild.org/

• What Should You Wear to Play Hickory Golf?

(The Hickory Hacker, YouTube) https://youtu.be/VBZz91ySQ_Y