Mens' neckwear, 1800 to 1899

- cathylane1118

- Feb 27, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 13, 2023

This article is an extension of two larger Hickory Lane projects: Golf Fashion for Female Golfers and Spectators, 1800–1899 and Golf Fashion for Male Golfers and Spectators, 1800–1899. These are in-depth, illustrated articles created to help featherie and gutty golfers pull together era-appropriate clothing. Each decade has its own write-up, and each write-up offers specifics on everything from hats to shoes and every piece of clothing in between.

Neckwear is an easy and inexpensive way to give your historic golf outfit just the right flair. It’s easy to replicate with modern materials, and you can even purchase some decade-specific ties and cravats online on sites like Historical Emporium. The advice offered here will focus on the proper neckwear for the end of the featherie era and the length of the gutty era (approximately 1800–1899).

1800–1820: The linen or silk cravat reigned during this period. It was a style available to different classes of people, as it is simply a triangle of muslin (ideally starched), folded into a band on the diagonal, centered on the front of the neck, wrapped around to the back of the neck, then around to the front again, where it is tied in any number of ways. The highly starched and intricately knotted cravat was the style for the upper crust.

A stock (below), a pre-folded or pre-tied strip of cloth that closes in the back with a buckle or a hook-and-eye, was a ready-made substitute. Sometimes stocks also had pre-tied bows attached to them.

Early 1800s stock

White cravats and stocks were worn over tall, stiff collars during this period. Black or sometimes colored neckwear became more common. A man’s selection of knot, color, and fabric pattern became a means of self-expression.

Cravats could be tied in many different ways.

How do you tie the perfect cravat? There are many tutorials on YouTube, or go old school and read The Art of Tying the Cravat, published in 1828, which shares 32 different styles. (The author’s names are Baron Emile de l’Empesé, Conte della Salda, and H. LeBlanc, which translate, respectively, to Baron Starch, Count Starched, and H. White—a cheeky team indeed.)

There are also tips for wearing cravats, including how to sleep in one, should that become necessary.

1830s neckwear

1830s: The high-collared jackets popular at this time hid large and complicated cravats. So new styles of neckwear started to emerge: the bow tie, scarves and neckerchiefs (more associated with working classes—a square of fabric folded into a triangle and tied in a variety of ways; this tied style emerges in golf fashion again at the end of the century), the ascot, and the four-in-hand or long tie. Some cravats were more like tubes with no bow or knot in front, while others were tied in some version of a bow. Neckwear switched from white to black or colors for daywear.

Also new at this time was the detachable collar, which allowed one's collar to be highly starched while the body of your shirt could remain more comfortable. Styles and shapes of these collars were myriad, which gave wearers even more options.

1840s neckwear

1840s: White neckwear was now reserved for evening wear, while black or colored/patterned neckwear was common for daytime. Collars were upstanding, usually with the front tips folded down. The neckband was narrower, but the bow or knot was very large. A scarf could be knotted loosely and fitted into the opening of the waistcoat and fixed with a pin. Very large, flat, and horizontal bow ties were popular.

1850s neckwear

1850s: During this decade, tall, stiff collars lost height; softer, turned down collars began to emerge. While a cravat/stickpin combo or a large bow tie were still popular choices, a longer vertical tie had become popular attire, especially for leisure/sporting activities. These ties were practical because they stayed in place and didn’t restrict movement. Bow ties became smaller by the end of the decade.

Westward Ho! (1869) photo shows a variety of neckwear styles.

Leith photo (1867) also shows a range of neckwear and collars.

1860s: Starched shirt collars were lower still and sometimes turned down in the front. Working men would have worn a banded collar, club collar, or rounded collar white shirt. Cravats were now made from a narrow band of fabric, usually less than an inch wide. These were tied in front as a small, flat bow, or knotted and fixed with a pin. Longer neckties were also popular.

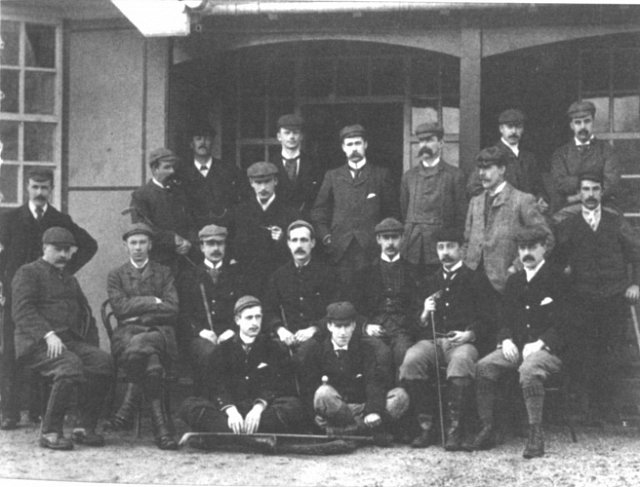

There are many neckwear styles in this 1870 Rose Club collage (St. Andrews).

1870s neckwear examples

1870s: Mass production of cloth and clothing meant that ready-made clothing of all types was much more available and affordable. Upstanding collars were low, and many men wore collars that folded over like that of a modern men's dress shirt. The four-in-hand tie (the same knot used today throughout the Western world) and ascots were popular.

Ties were still available in the bow tie style, as was the popular black string bow tie, made from a black silk ribbon, about an inch high and a yard long.

1885 sartorial review. Note the many styles of detachable collars.

1885 neckwear examples

1880s: Upstanding collars and folded-over collars were still popular, and these would be worn with a bow tie or four-in-hand tie. The string tie and ascot were also still in the running. Jackets were buttoned high, leaving little room for neckwear, so ties shrunk in size.

A wide range of 1890s neckwear examples. Upper left: Alex Smith, Willie Smith, and (standing) William Law Anderson, 1895; upper right: late 1890s St. Andrews; bottom: Headingley, 1898.

1890s: A mix of high collars and folded-over collars were worn. The long tie with the four-in-hand knot reigned supreme. But the bow tie, ascot, and knotted scarf were also frequently worn.

Post-1900: It goes without saying that the detachable collars introduced in the 1830s were worn with collarless shirts. For work or more casual situations, men wore the collarless shirt without the detachable collar but would still wrap a scarf-like tie around the neck of the shirt, knot it, and tuck its tails in between button gaps. This style was popular among working-class professionals and bridged the gap from the gutty era into the transitional era when the Haskell ball first came on the scene.

Four-time U.S. Open winner Willie Anderson (left) and Alex Smith in 1905. Note the tucked-in ties. They are likely wearing three- or four-button work shirts or henley-style shirts. Compare this style to the much more formal fashion these same two golfers are wearing in the 1895 photo shown with the 1890s entry above. Why not dispense with the tie altogether? In part, there was an expectation to be dressed up on the course. But Hickory Hacker Christian Williams makes a very good point. "As good as they were at playing golf, they were still considered working class and paid as such, so I think something else we're seeing in these photos is golfers looking the best they can within their meager means," Williams notes.

Hickory Hacker Christian Williams adopts this style for gutty golf in the summer because it's period correct and is also more comfortable in warmer weather. He gets his scarves/handkerchiefs here. He wears long-sleeve, linen henley shirts for warmer weather.

Sources

Hickory Hacker, https://www.youtube.com/c/thehickoryhacker and https://www.hickoryhacker.com/play-hickory-golf. For specific "what to wear" advice, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VBZz91ySQ_Y&t=1806s

Historical Emporium (sells various versions of ties)

Ellie Valsin (Tumbler)

teainateacup.wordpress.com/tag/mens-neckwear/

twonerdyhistorygirls.blogspot.com/2018/04/the-neckcloth-part-2.html

Victoria & Albert Museum

Vintage Dancer

Additional reading

Neckclothitania, an 1818 satirical leaflet, inspired by the dandy culture obsessed with Beau Brummel and his cravats. Attempt to read the digital version at

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Neckclothitania_or_Tietania_an_essay_on/CjRcAAAAQAAJ?hl=en